Language forms an important aspect of present-day filmmaking. The use of spoken language helps to tell a story where visuals would possibly fall short. It can convey certain emotions, and display a certain atmosphere. These are most frequently languages we already are familiar with. However some films or television series prefer to spice things up by using constructed languages, so-called conlangs.

(Re)Constructed?

Languages are similar to living organisms. They evolve throughout time – changing their pronunciation, adding new words to their lexicon, and/or adapting their grammar. They are shaped through interaction with other languages or certain events that occur around them. And just like living organisms, languages die.

Some of these dead languages are windows to the past, as there might be myriads of written documents available that hold intricate information of what was once a living tongue. Latin could be considered as such.

However, not all dead languages were as fortunate as Latin. The East Germanic Gothic, for example, did not offer an abundance of written evidence. A peek into this particular language would rely on a few indirectly related sources, merely revealing scattered, almost unintelligible fragments. A number of linguists in the field of comparative linguistics accepted the challenge of reconstructing the Gothic language by means of these few remaining documents. However, a true revival or reconstruction of the language has not occurred thus far.

There are on the other hand certain languages that share a similar reconstruction, but rather than carrying any historical value, they serve the purpose of entertainment. They are a daydream to the future, or an anecdote to the past that has never been. They are pieced together by elements from already existing languages, as if forming a new mosaic using old stones. It reveals a picture of an entirely new language, which grammar remains relatively unknown to everyone, except for its creator and its performers. Some well-known examples of such languages are Klingon, Elvish, Dóthraki, High Valyrian, Na’vi and Esperanto.

Most of the above mentioned languages are not actually used for everyday communication, except for Esperanto (although I do believe Klingon did live up to the vogue of actually being spoken within a very niche but relatively numerous group of people). These are constructed languages, also known under term “a priori languages”. They are defined as such because none of these languages contain a lexicon that would be related to another already existing language. One could stipulate that they are created from scratch. But how would one be able to create a language from scratch? Let’s find out!

Think Big!

Creating a new language is not a mere accumulation of new invented words. If that were the case, then most children would be linguistic visionaries. For a constructed language (conlang) to properly function one needs to take into account some very important factors.

Paint yourself a backdrop

In order to create a conlang, one has to truly immers oneself into the world of make-believe. Sit back and create an imaginary society. Your society will have fought wars, formed clans, discovered new land, created a social hierarchy, and so on. They have their own fictional history, that should be considered as real for them as the actual reality is for the creator. One should also question the dimensions of the language. How would these people sound? On what part of the planet would they live? Language is very complex and that could imply that the conlang is not only spoken but perhaps also signed. Hard to imagine? Think about a society based on the aesthetics of H.P. Lovecraft’s creature Cthulhu, except less scary, without any mouths and vocal tracts. They would not be able to verbally communicate with each other and it would therefore make sense to use sign language instead. Just imagine how complex this sign language could be as they possibly have around 8 tentacles that can move simultaneously. A good example to illustrate this possible complexity can be observed in the film Arrival (2016), where an octopus-like alien species attempts communicate with human beings without any vocal utterances. Instead they use something which appears to be ink circles to simultaneously convey the past, the present, and the future. Good luck trying to master that language.

Linguistics 101

Now let’s talk grammar! Every language needs to have a grammar, or we would not be able to make sense of any signed movement or spoken utterance. Languages would just consist of scattered and incoherent fragments of movements and sounds. It might be most practical to first start looking into the linguistic branch that studies the smallest meaningful units of a language, namely phonology.

Phonology

Imagining that the new conlang will be a spoken language, phonology might be an interesting place to start. Simply explained, phonology is a branch of linguistics that studies the science of speech sounds with reference to the history and theory of sound changes in a language or in two or more related languages. Most languages have both consonants and vowels.

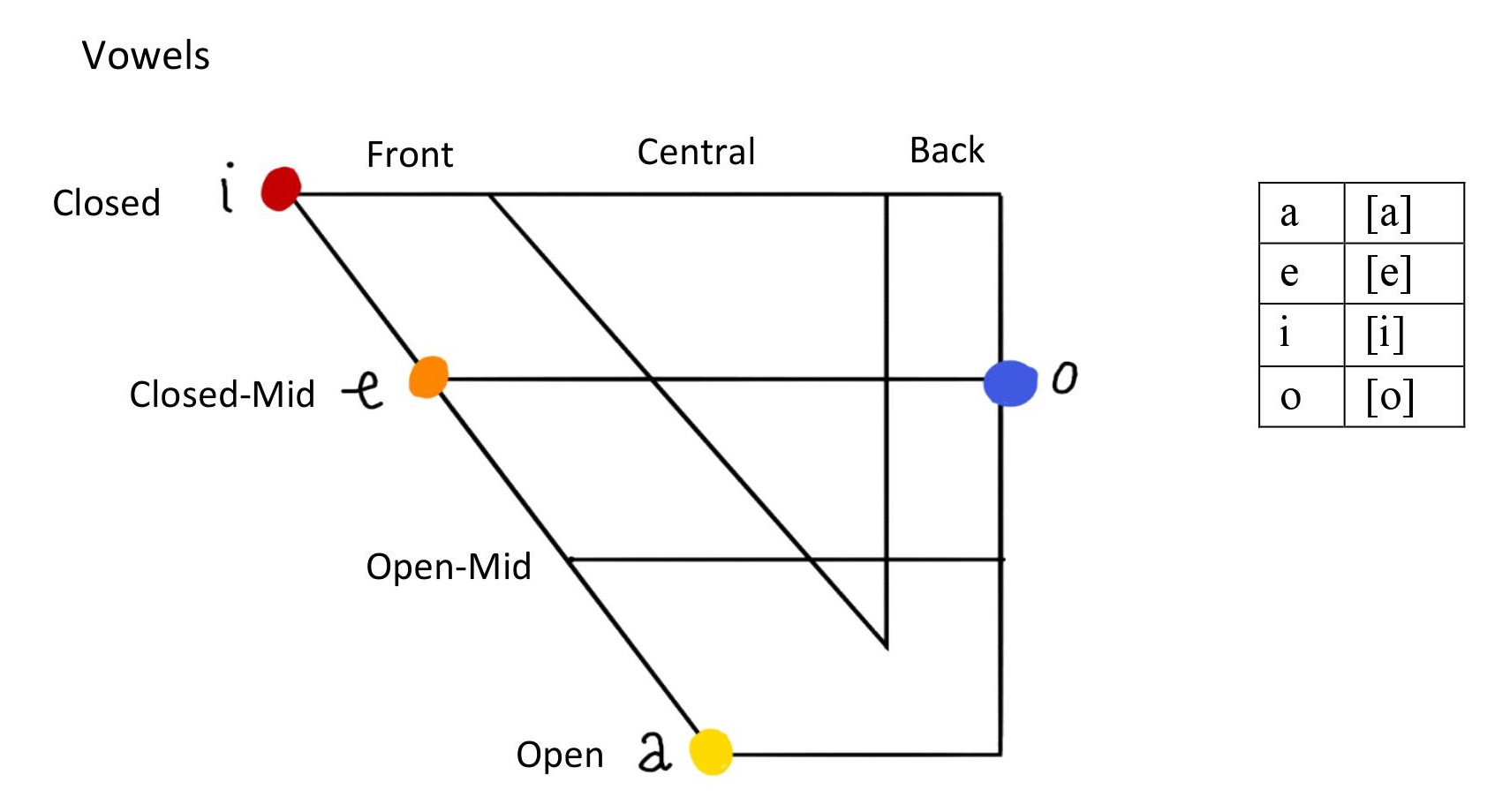

English for example has 21 consonants and 5 vowels. It becomes a little more complex as there actually appear to be 20 vowel sounds. This means that there are 12 pure vowel sounds, and 8 glides. The latter are most frequently known under the term diphthongs. Let’s analyse a conlang such as Dóthraki, created for the television show Game of Thrones. Dóthraki has 22 consonants and only 4 vowels.

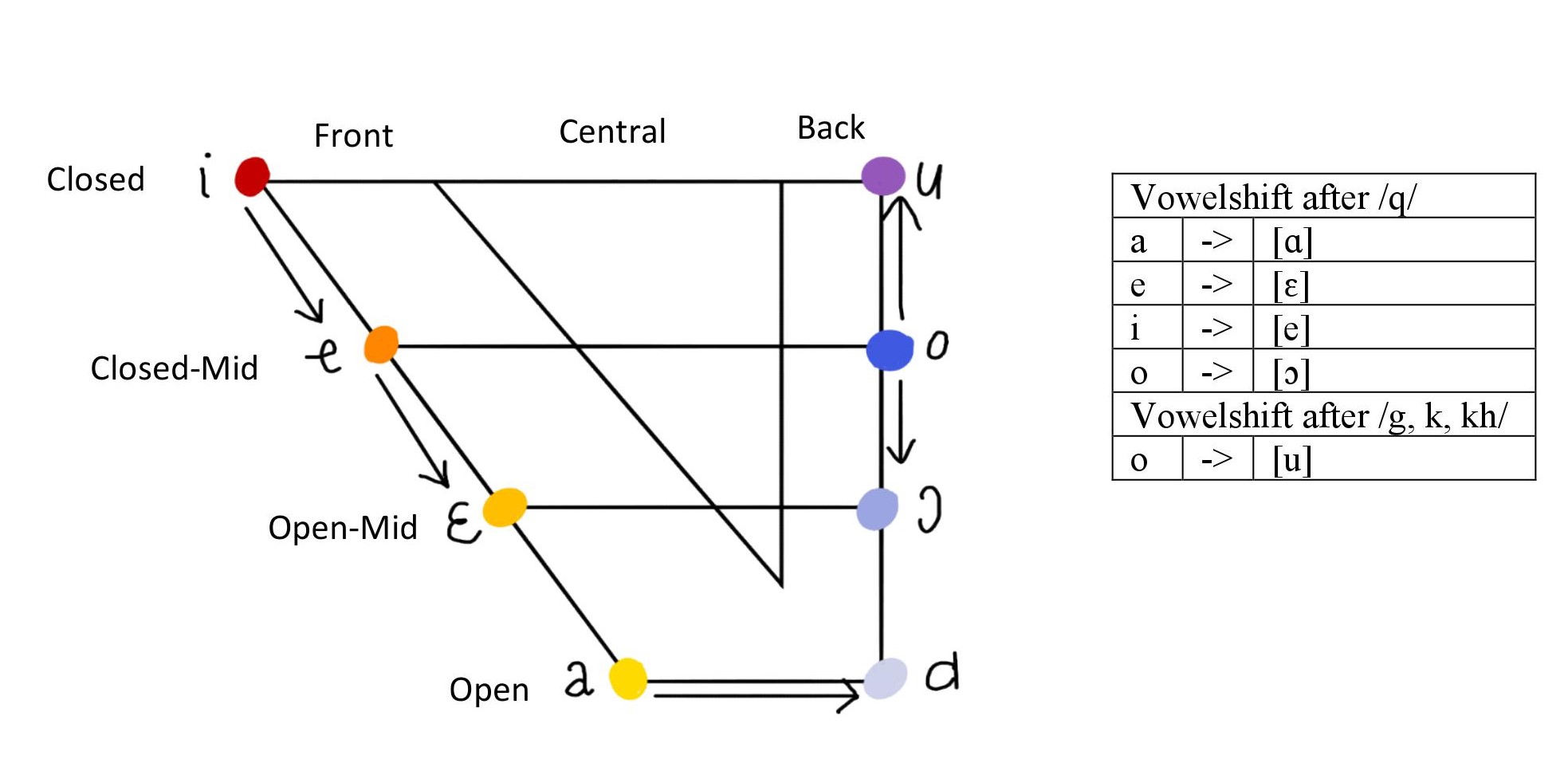

The vowels of Dóthraki seem a little less complicated than those of English. Dóthraki does not have any diphthongs nor long vowels. The only aspect that might be slightly confusing for those analysing it, is the vowel shift. A vowel becomes less fronted and more open after the consonant /q/. And if the vowel [o] is positioned after /g, k, kh/ it will start to sound more like a [u] as in the English word for shoe.

This is however a very common phenomenon in many languages. It might seem complex, but speakers of a language that exhibits such characteristics are often not even aware of this phenomenon. There are of course more known examples of vowel shifts such as the Great Vowel Shift in English, where the entire language shifted the sounds of its vowels in a more drastic manner.

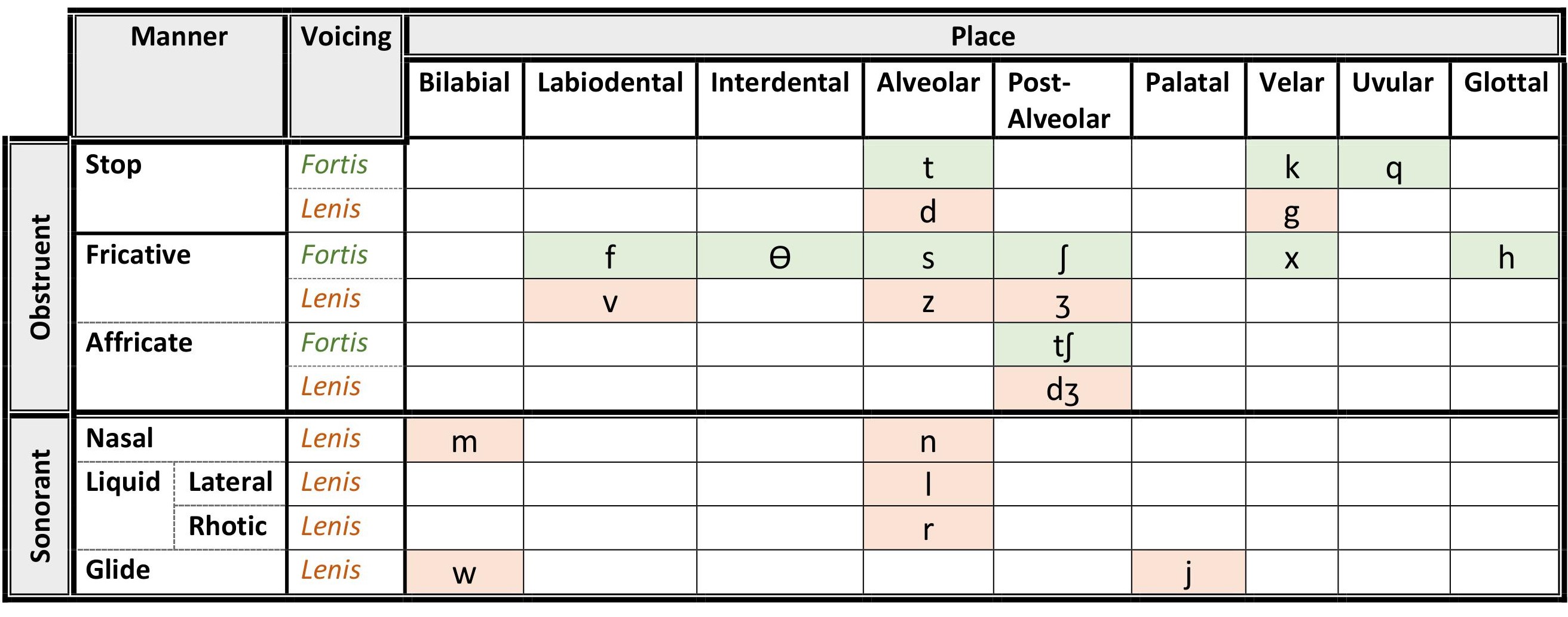

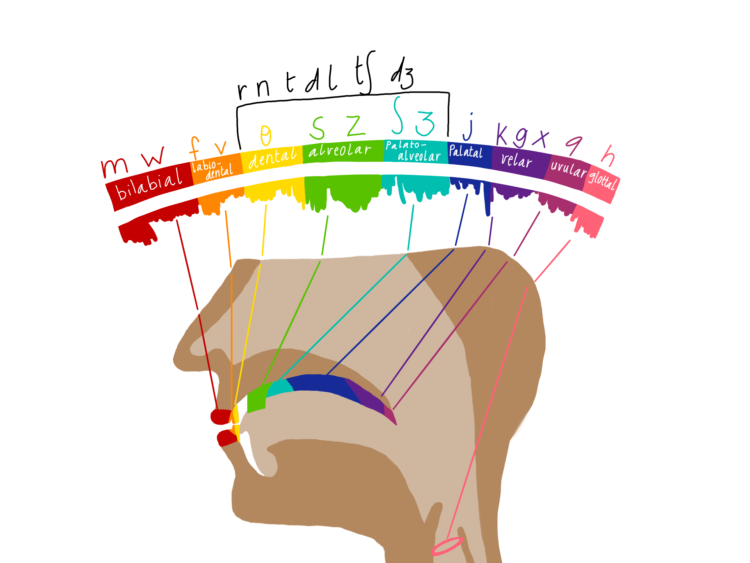

Phonology can be rather dense and hard to grasp, but this difficult terminology is often a useful reference to the manner, voicing and place of the pronunciation of a sound in the oral cavity. To provide a better insight concerning the positioning of sounds in the oral cavity, I illustrated a dummy for the consonants and an abstract mouth-shaped scheme for the vowels containing indications of the places in the mouth/throat where each sound should be produced. However these illustrations are mere abstract visualisations of pronunciation. No information is provided on where to put the stress, or what intonation the language should use. Should it be a tone language such as Mandarin, or not? These are aspects to reflect upon when one would aspire to create a conlang. By studying the sounds of a language so carefully, the creator of a conlang or the actor who has to perform the language can acquire a good sense of how a certain sound should be pronounced. For example, this can cause conlangs to have an arabic, slavic, italian, or spanish, ring to it. It’s perhaps self-understood as the sounds used for conlangs are often inspired by the sounds that already exist in another language.

Morphology

Once the phonological aspects are understood, and potentially created, it would not hurt to take a closer look at the possible morphology of the conlang. Morphology can be shortly defined as a branch of linguistics that is occupied with the formation of words and its relation to other words in the same language. A noun for example could mean one thing, but by adding a prefix, a suffix, or an interfix, the meaning of the word might shift entirely. To illustrate this, let’s take a look at Daenerys’ middle name, Stormborn. Her mother tongue is High Valyrian and thus her middle name would be translated to Jelmazmo. Peterson, the creator of Dóthraki and High Valyrian, first started with the invention of the word that would resemble “wind”. He came up with jelmio. Afterwards he started reflecting about a word for a greater type of wind, a storm. This word would become a derivative of jelmio, namely jelmazma meaning “great wind”. Dany’s middle name contains another vowel in the end compared to the root for storm, and this actually signifies a genitive case (similar to other case languages such as Latin or German). Thus Dany’s name could be translated as “of the storm”. One can even start to analyse the composition of the word jelmio and jelmazma. It could be argued that jel could mean the same thing as “air”, the morphemes “mio” and “mazma” could perhaps be translated to “small” and “big”. In that sense the words could be considered compound nouns and by changing one of them, the entire meaning of the word might shift.

Syntax

Syntax could be defined as a study of linguistics which attempts to clarify and organise relations between the words in a sentence as well as the order they are presented in. When creating a conlang it would be useful to think about the word order of the language. About 42% of all registered languages in the world have an SVO word order, meaning that the Subject is followed by a Verb and then an Object. In the case of High Valyrian an SOV word order is applied. This too, is a common word order as 45% of the registered languages also use of this order. To shortly refer back to morphology, it is interesting to note that High Valyrian has 8 grammatical cases. Whenever a language functions with a grammatical case system, it implies that the sentences are likely to contain fewer prepositions. Prepositions are redundant in such languages because the case ending often already refers to a sense of place/direction/action/position. Sentences are thus often shorter and more to the point. It makes sense for a conlang such as High Valyrian to use grammatical cases. It is mainly used by people who are positioned in the upper part of the social hierarchy such as rulers, priests, scholars,etc. So the language should be as informative and powerful as possible in the most economic amount of words. The “plebs” will use a more colloquial variant called Low Valyrian. One last aspect of the syntax is its use of determiners (this,that…). High Valyrian uses 3 different types of determiners. “This” is used to refer to an object or person that is close to the speaker, “that” is used to an object or person that is a tad bit distanced from the speaker, and there is another “that” which refers to something that is far away beyond the eyesight of the speaker. This could be of practical use for example when referring to predictions in warfare or even in a more symbolic sense, in denigrating or marginalising a certain type of people.

Miscellaneous Elements

Writing systems

When all the linguistics have been sorted out, it’s time to think about the more trivial aspects of a conlang, such as for example which writing system the language should have. There are many different writing systems in the world that could be used as a reference for the creation of a conlang. The writing system in which this article is written would conform to an alphabetic writing system. This is a system which uses unique characters for vowels and consonants. It’s by far not the only writing system. There are is Abjad, which uses unique characters only for consonants. A syllabary writing system such as the Japanese Katakana uses a main glyph for a consonant and an addition for a vowel. Then there is also a logographic writing system such as the Chinese Hanzi and the Japanese Kanji. This latter writing system uses a glyph that is a representation of an entire word, or a part of a word. When creating a conlang it is perhaps a bit trivial to also create a complex writing system if it only is supposed to be spoken, but it offers an interesting addition to the character of your conlang.

Lexicon

The next miscellaneous would be lexicon. How big do you want your conlang to be, in other words: how big should the vocabulary be of the conlang? It all depends on your patience, passion, and perseverance. As I mentioned in the introduction, a language is never truly finished – it changes constantly. So creating a conlang could be a work of a lifetime, but remember, one must imagine Sisyphus happy. Peterson revealed that Dóthraki, his biggest language, only contains 4000 words. This might seem like a lot, but considering for instance German and its estimated 330 000 words, 4000 is not quite as flabbergasting a number.

Mastering any language, a noble dream?

Creating a conlang is a very intricate process that requires a lot of patience, research, linguistic knowledge, perseverance, passion, you name it. But it would never hurt to give it a try. It does not have to be very complex, as you can make it entirely your own. What will happen nevertheless as one engages in such a process, is the acquirement of a profound linguistic knowledge. Even if the conlang was not a great success, the attempt will definitely pave the road to a better understanding of any other language that already exists in the world. Learning any language would be as the Dóthraki would say “che dothras che drivos“, you either “ride or die”.

Siste podcaster

-

Tal- og skriftspråk

Tema for ukens sending er tal- og skriftspråk! Det blir ordskifte rundt om det finnes et standardtalemål i Norge eller ikke. Julia tar med oss hjem til Sverige der diskusjonen rundt et standardtalemål ikke er så vanskelig som den er her i Norge, eller er den virkelig det? Vi ser på en skriftform der talemålet ofte tar mer plass en i andre type sammenheng - nemlig språk på sociale medier. God lytt! I studio: Julia Zsiga, Øystein Sandve og Vilde Galtung Ordskifte er programmet for deg som har en mening om hva som er riktig og hva som er galt å si. Vi tar for oss språklige finurligheter og grunnen til at du snakker akkurat slik som du gjør. Hvis du føler at det du trenger i radiouniverset ditt er et språkprogram med et friskt pust, er Ordskifte programmet for deg!

Last ned episoden

Last ned episoden